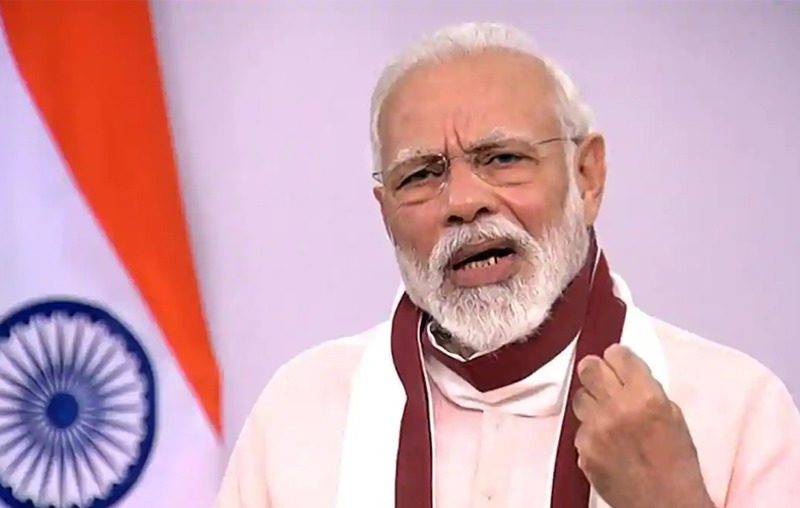

The making of Brand Narendra Modi

Narendra Modi is a transition from politician to brand that has been carefully charted out. From a raging Hindu nationalist to India’s most popular prime ministerial candidate — if one were to go by the various exit polls and pre-poll surveys, that is — the evolution of Brand Modi has been spectacular.

That said, Brand Narendra Modi started out on a weak wicket, in 2002, when he gained a place in national consciousness against the backdrop of the Godhra riots. His first tryst with public awareness outside of Gujarat gained him more detractors than supporters. He was branded a right-wing radical. And yet, he was re-elected by the state three times since then (2002, 2007, and 2012) adding credence to his claim of being the development boy of Gujarat. Vibrant Gujarat, Gujarat’s annual investment event, the high profile Tata Nano project shift from West Bengal to Gujarat almost overnight were some of the events that ensured that he steadily carved himself a place at the national level despite being a regional player. His own meteoric rise to fame over the past 12 years burnished his messianic positioning, making him uniquely qualified to lead BJP’s Lok Sabha campaign for 2014.

Political and brand consultants say the branding of Modi in the run-up to the 2014 elections hinged on one simple proposition: to turn people’s attention away from his early political history to the more recent economic transformation of the state of Gujarat, to position him as the harbinger of economic growth —

Which eventually became the overall theme of BJP’s campaign.

“The starting point was the anger in people, the angst against corruption and the Central Government. The campaign had three objectives: to reflect the mood of the nation, show the electorate the possibilities of a better life and give them a leader they can trust,” says Piyush Goyal, BJP national treasurer, and a key player in Modi’s marketing crack team.

Goyal’s campaign summation is further corroborated by one of the brand-building partners. “Last year, during the Delhi assembly election time, as far as national elections were concerned the idea was to attack the Congress and then move forward. But towards the end of last year, it became apparent that Congress was getting slammed from all quarters. There was no point wasting time there. Besides, today’s voter is not interested in this slamming match. He wants to know what would you (his elected representative) do for him. It was decided then that the campaign must arouse nationalistic, patriotic fervor among the voters,” says Rajshekhar Malaviya, CEO, Promodome Communications, one of the agencies working on the Modi campaign.

The shift in campaign strategy gave Modi the opportunity to build on the development-man image and dull his Hindutva agenda by a shade.

“Being a Hindu nationalist is a double-edged sword,” says Santosh Desai, MD and CEO, Future Brands, and a very avid political observer. “The strength is that you are seen as a voice of the majority Hindu consciousness. The flip side is, Hindutva is not a strategy that can win an election in India. As an undercurrent, it is motivating but it cannot be the primary benefit. The primary idea has to be about the nation’s development,” he says. That is imperative if only to give BJP’s Mission 272+ any chance of success.

It is not to say that Modi discarded his Hindu hardliner image completely. The man who famously called himself a Hindu nationalist wore his saffron colors with pride but did not let it rule his conversation. There was definite subtlety. Like his refusal to wear a skull cap and pander to symbolism. And yet the message, always the same: that he may not wear the cap but he does respect it, which is a lot more important.

The look and feel

Modi has achieved something interesting. He made his aggression seem decisive and hence desirable. Samit Sinha, managing partner, Alchemist Brand Consulting, says, “Culturally, Indians have always been quite content to be ruled by a powerful king-figure, rather than the more abstract idea of self-rule, so centralized authority (or even a benevolent dictator) is not at all an anathema for most Indians. Centralization of power and determined authoritarianism could well be seen by today’s India as the need of the hour and an attractive antidote against economic stagnation. Hence, this time the pitch is for Modi Sarkar not BJP Sarkar.”

The look and feel are as much a part of the package as the sophistry. The bespoke kurta, the Movado watch, Bvlgari spectacles, and the Mont Blanc pen set him quite apart from the ‘regular’ Indian politician. Modi’s obvious delight in dressing well resonates with a section of the electorate that values opportunity and personal growth and progress above divisive politics and chicanery. The Modi sarkar pitch is actually not so novel if one went by BJP’s campaign history. In 1996, a similar call — “Sabko dekha bari bari, abki bari Atal Bihari” — had rung out. But here’s the difference.

The 1996 slogan was spun around Atal Bihari Vajpayee’s turn at governance without spelling out what that entailed. This time, Modi’s campaign managers have taken the nation’s problems and connected them with their own proposition of change: “Bahut ho Gayi lehenga ki maar, ab ki Baar Modi sarkar, a henge Naari pe Atyachaar, ab ki Baar Modi Sarkar”. Such has been the popularity of this couplet — thanks largely to social media — that it has assumed the “national time-pass” status, being liked, tagged, and forwarded freely.

The media mix

Brand Modi has gone the whole hog on its media delivery with advertising on radio, television (particularly during the IPL cricket matches), print, hoardings, and bus panels, in addition to posters, rallies, and public speeches — de rigueur during political campaigning. Some of the matters addressed in the campaign include the creation of jobs, better education, and the removal of corruption. The campaign has been customized for each state as well as urban and rural centers. Contrary to the commonly held view, Modi’s brand team has leveraged technology for micro-targeting even in media-dark rural areas.

In September-October 2013 and later in January, BJP conducted a study on what should be the messaging and the medium for the campaign. “For instance, we found that 30,000 villages of UP and Bihar were media-dark, with no TV, print or radio,” says Goyal. In such rural areas, for instance, the party sent out hundreds of vehicles with LED screens mounted on them. These screens showed party ads, Modi’s speeches, and the BJP manifesto on it. “It was done in a systematic manner and every rupee was thoughtfully spent,” Goyal adds.

Human banners and placards dominated below-the-line rally promotions, along with off-line activation. For instance, music bands were unleashed in public places, which started by singing some popular numbers to collect a crowd and then switched to singing Modi-and BJP-theme songs. The key agencies involved in these exercises included Soho Square (creative) and Madison Media (media planning and buying). Their efforts got a boost from the so-called Modi supporters hawking everything from Modi masks to USB drives online.

But the true hero of the story has been public relations (PR). Experts say while social media won’t ring the votes in, it has the power to generate positive PR in the media. “Social media is great to stir up controversies, giving people a sense of participation. But once these comments on social media are picked up and magnified on TV and newspapers, they become discussion points,” says Nilanjan Mukhopadhyay, author of Modi’s biography. “People know Modi is a great doer, but ask them what has he done, and they may not be able to answer. This is a bullet point driven campaign where Modi is discussed and debated in 140 characters,” he adds.

In another four days, we will know if the electorate was swayed by this unprecedented-in-scale political campaign. For the moment, Narendra Modi and his team can revel in the fact that the message was communicated, heard, and possibly even internalized in the exact fashion they intended it to be.